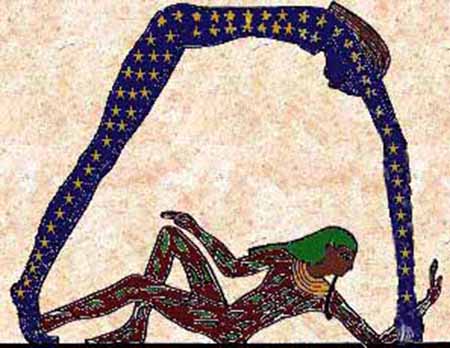

Nuit: Egyptian Sky Goddess

Shu was the god of dry winds. Tefnut was the lunar goddess of moisture and humidity. Atum, the self-created god who arose from Nu, the nothingness that preceded the world, created them from his own blood. Atum commanded his children to create the Universe from the void. After they completed the task, Atum was said to have been so ecstatic at their work he shed copious tears of joy. These tears became human beings. The sudden presence of these mortals proved problematic for Atum, Shu and Tefnut as the humans had no place to reside. So, Shu and Tefnut mated to produce Geb, the Earth god, and Nuit,. goddess of the sky. Although Nuit and Geb were commanded to create a home for the humans, they became so enraptured by one another that they refused to separate. The intensity of their intimacy so disturbed Atum that he forcefully pulled them apart so that Nuit was fixed high above Geb. Furthermore, he forbade Nuit from giving birth on any day of the year to punish her for her initial refusal to part from Geb. (Geb went unpunished.) This restriction caused Nuit great distress, for she and Geb had produced five children, all of whom remained trapped within their mother. Fortunately, Thoth, the god of wisdom, persuaded the moon god Iah to produce enough moonlight from which to create five extra days apart from the fixed calendar. During these days, inserted in July, Nuit delivered five children, one on each day. On these days she gave birth to Osiris, God of the Gods and the Underworld; Isis, Goddess of magic; Set, God of deserts and evil; Horus, God of War and Nephtys, goddess of water.

Ever since her forced separation from Geb, Nuit arched her body over the world. Fully nude, either a hand or foot marks each cardinal point and her body is adorned with stars. When the Sun god Ra traverses the sky, these stars become invisible. However, at the end of each day, Nuit swallows Ra and her bodily stars become visible. Each morning, Ra is issued forth from her womb, the birth of a new day. Nuit also serves as the impenetrable barrier separating the disordered chaos of the Universe from the well ordered world below.

There she remains, sometimes supported by Shu to give her a respite from the strain and to ensure she maintains a fair distance from Geb. At other times she is alone and ensures that day and night follow one another and never overlap. Though we can never look directly upon her, we shall always have the chance to admire the stars that cover her body.

THE SOUTHWORTH PLANETARIUM

207-780-4249 www.usm.maine.edu/planet

70 Falmouth Street Portland, Maine 04103

43.6667° N 70.2667° W

Altitude: 10 feet below sea level

Founded January 1970

Julian Date: 2459235.18

2020-2021: LXXV

THE DAILY ASTRONOMER

Wednesday, January 20, 2021

Wednesday, January 20, 2021

Exploratorium X: Seeing the Two Hypathias

Location

Alexandria, Egypt

Time

410 A.D.

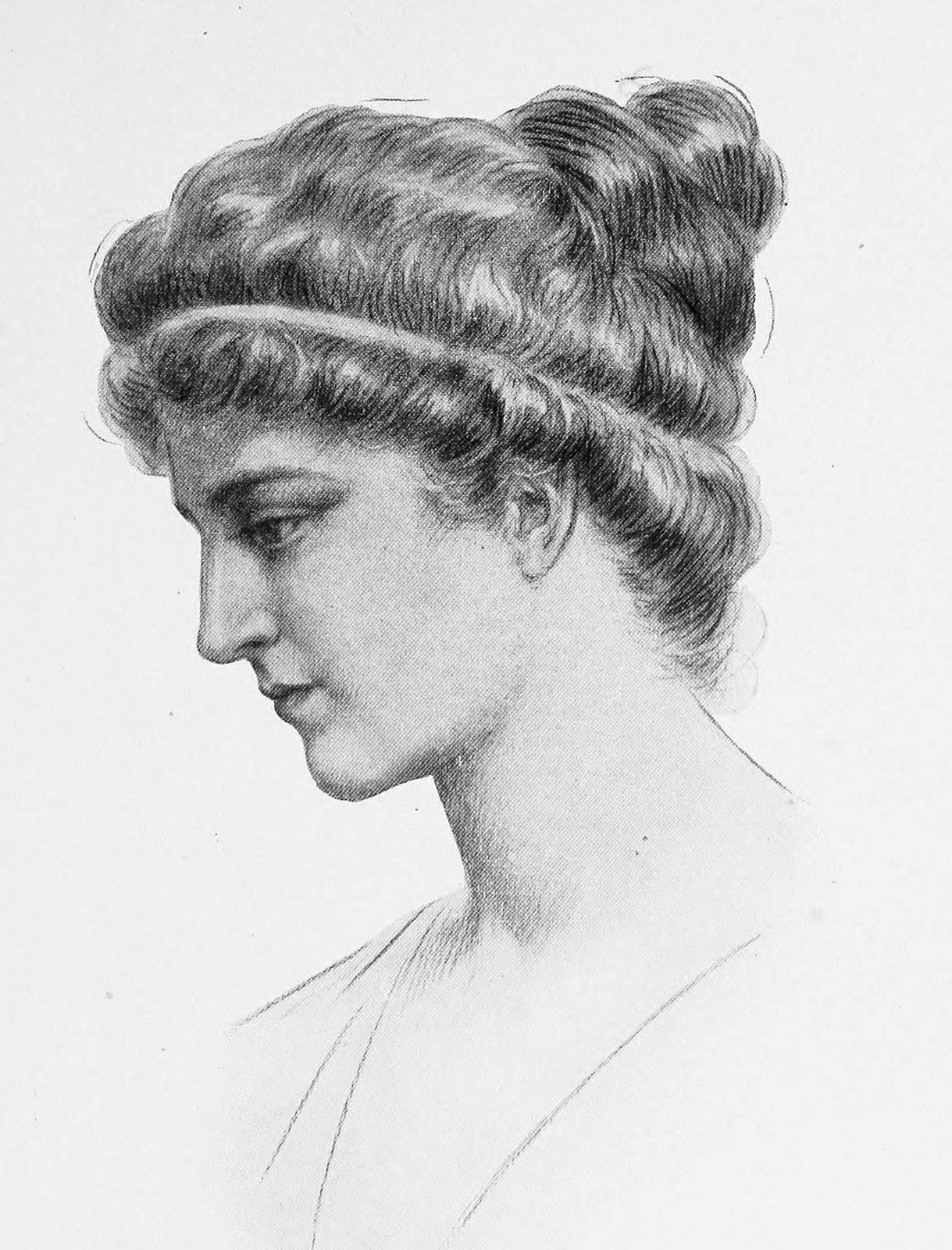

It must be said that Hypathia of Alexandria's (350 - 415 AD) most notable portraits, both drawn in the 19th century, are as beguiling as they are inaccurate. Charles William Mitchell's Hypathia depicts her nude form strategically concealed by flowing tresses. However, Jules Maurice Gaspard's Hypathia is a facial profile: a serene countenance with eyes affixed on a sight we, ourselves, cannot observe. Whereas Mitchell's Hypathia suggests the coquette who refuses to gratify the desires she arouses, Gaspard's less deprecating portrait shows Hypathia as Goddess: a wise Athena scrutinizing a puzzling world or a benevolent Rhea beholding infant gods in repose. Yet, we understand that both men post-dated their subject by more than a millennium, and instead of capturing Hypathia, were merely crafting their own Galateas. Their creations were as divorced from the historical Hypathia in character as they, themselves, were displaced from her in time. Even the Hypathia that Raphael included in his "School of Athens" masterpiece is little more than speculation alloyed with paternal notions of feminine beauty.

We can never know what she would have thought of these posthumous depictions. Frivolous, most likely; fanciful male notions that might have occasioned her amusement as much as evoked her scorn. The art works' appeal was merely that of the superficial loveliness all too transitory in the human form. These images possessed none of the beauty she most highly esteemed: that of the cosmos entire. For hers was a realm capped by boundless skies and circumscribed by unsounded deeps. A world that only reluctantly yielded its deepest secrets through persistent contemplation by the philosophers, mathematicians, and astronomers of Antiquity's Golden Age.

That Hypathia would distinguish herself as philosopher, mathematician and astronomer was not uncommon, for in the late 4th-early 5th centuries, such pursuits were inextricably intertwined: aspects of the philosophy seeking to demystify nature itself. That a woman in the ancient world would have risen to such an exalted height was almost pre-ordained, for her father, the famed Alexandria mathematician Theon, sought to cultivate, rather than quell, the astonishing mathematical aptitude that his young daughter evinced. Through his instruction alone -nothing is known of her mother-Hypatia became well versed in not only mathematics, but in astronomy, philosophy, literature, the arts, and even physical education. Historians who regarded Theon kindly considered this holistic education to have been evidence of a father's ardent love. His detractors disparaged him as a tyrant who drove his beleaguered daughter mercilessly to become "the perfect human being."

Theon of Alexandria

Though his motives remain disputed, the results of his efforts are certain: an astronomer-mathematician of the highest order. As she matured, Hypathia assisted her father in the editing of both Euclid's elements, the fundamental text of Euclidean geometry, and Ptolemy's "Almagest," one of the principal astronomical texts. She also composed commentaries on Ptolemy's "Handy Tables," compilations of astronomical observations. These commentaries, like those she wrote for Diophantus' "Aritmetica" and Apollonius's "Conics," are no longer extant. We only know of her through the scant writings of contemporaries and those of subsequent generations, both foes and admirers.

We know that she eventually became associated with the Platonist school at Alexandria and was the quintessential "neoplatonist," a philosopher who taught that the Universe was founded on an objective reality whose true nature humans could never truly discern. It was argued that inquiry was essential in ascertaining nature's visible machinations, but that mortality, itself, precluded comprehension of the physical whole. (Modern day cosmologists, exasperated by dark energy, might relate well to that principle.) Apart from engendering a nihilistic gloom, Hypathia's neoplatonist philosophy evoked in her an inexhaustible wonderment. There would always exist grander mysteries to which even the most formidable mind would remain unequal. The horizons would remain perpetually elusive and therefore mystical. But, ultimately, or so they believed, these tireless rational inquiries would unite the human mind with the very essence of the divine, likely in remote posterity.

Hypathia imparted that love of inquiry and joy of wonderment to her students, for it was as a teacher that she truly established her reputation in Alexandria. (We have precious little information pertaining to any of her research, apart from the augmentations she offered to the works of Ptolemy, Apollonius, and the others.) She was said to have exemplified the traits that define the most gifted of teachers: an ability to convey the most extensive knowledge and expound on the profoundest philosophies in a manner that was said to have induced a sublime delight on her students. In so doing, she also commanded in them a respect verging on reverence. One of her most noteworthy pupils, the Bishop Synesius, once confided to a friend that to be a student of Hypathia's was to be in the company of the one person made privy to nature's deepest secrets.

Here, Synesius spoke to the manner by which Hypathia, more than any other neoplatonist, blended the power of scientific inquiry with philosophical ruminations and midwifed the birth of natural philosophy. The audacious notion that the human mind, itself, could divine the world's physical principles and ultimately identify the governing force actuating it all. The very same notion that would send Galileo before the inquisitors centuries later.

Like Galileo, Hypathia found herself embroiled in religious strife. Her conflict, however, pitted her ancient Paganism against the modern rise of Christianity. Centuries of mutual persecutions instilled hatred in both. Indifferent to such antipathies, Hypathia was known to have instructed Jews, Pagans and Christians alike in her newly crafted philosophy of scientific and astronomical inquiry. Seeking the divine in stellar configurations, planetary motions, and the complex language of mathematics: open to all worshippers.

Despite her determination to remain uninvolved in these battles, Hypathia found herself within a furious melee incited by a conflict between Orestes, Roman Governor of Alexandria, Cyril, Bishop of Alexandria. Hypathia was known as an ally of Orestes and blamed by many of Cyril followers for fomenting the discord between the two men. They distrusted the "philosopher's daughter" who they believed had practised the most sinister forms of divination and other unhallowed arts. Astronomy, then hardly distinct from astrology, was equated with the darkest magic. During a flash point in this conflict, Hypathia was caught in a violent mob and brutally murdered. Actual accounts of her slaying vary according to the agendas of the authors. What is known is that Hypathia of Alexandria was almost literally torn asunder in Alexandria in 415.

Some scholars cite her death as heralding the true end of Antiquity: the last edifice of Olympus to crumble before the conquering monotheists. Others assign less significance to Hypathia's murder, though they concede that her slaying attested to the predominance of the Christian Church over the ever weakening Paganism.

As is true with Hypathia's appearance, her true nature will remain forever unknown. She has become as mysterious as the nature she strove to comprehend. We are left only a figment of a philosopher who bestrode the heavens as freely as she wandered the Earth. One gifted with a formidable mind enlivened by the simple, but beautiful, notion that through profoundest contemplation even the loftiest, star-adorned heaven could be rendered accessible. And, this bold idea reverberates still through the subsequent centuries of tireless scrutiny of our cosmos: an idea conveyed by the mythical figure who beheld the horizons and from them fashioned the art of modern astronomy.

To subscribe or unsubscribe from the Daily Astronomer: