Socrates and Phaedrus: Why are you guys here?

For some reason, during today's excursion through the upper atmosphere, we're looking onto Socrates and Phaedrus. The once-great-now-divine Socrates and Phaedrus met outside Athens. Phaedrus had just left the home of Epicrates, an Athenian famous for hosting gatherings of prominent citizens. While at Epicrates' house, Phaedrus had listened to a speech on love delivered by Lysias, a son of Cephalus* and one of the ten celebrated Attic Orators. Socrates ardently desired to hear the speech. Knowing that Phaedrus' memory was prodigious and suspecting also that his protege had the speech concealed under his cloak, Socrates devoted a great deal of time trying to persuade Phaedrus to recite it for him. As always, Socrates eventually prevailed and Phaedrus delivered the speech to the best of his ability. However, we're watching them discussing another matter altogether: the story of Boreas and Orithyia.

Orithyia was an ancient Athenian princess, the daughter of King Erechtheus and Queen Praxithea. She was, as one might suspect, enchantingly beautiful and therefore desired by many men. Among her many suitors was Boreas, the North Wind. As soon as he looked upon her, he resolved to make her his wife. Initially, his pursuit was an honorable one. He attempted to seduce Orithyia and also to ask the King's permission to take her as his wife. However, Orithyia repelled his advances and the King, who knew the appalling story of Procne and Philomela, didn't trust Boreas because he, like the dreaded Tereus, was a northerner. Boreas didn't exactly accept these rejections philosophically. Boreas transformed himself into a dark cloud and enveloped Orithyia while she sat along the bank of the Ilisus River. He then ravished her and brought her up his northern abode, where she became his wife and eventually was transformed into the goddess of cold mountain winds.

During their walk outside Athens, Socrates and Phaedrus found themselves strolling along the Ilisus River. Phaedrus mentioned that they were both near the region of Orithyia's abduction. He then asked Socrates if he thought the tale was true. He, himself, was rather skeptical of the ancient legends and believed that his mentor, heralded by many as Athens' wisest citizen, would consider the tales merely fanciful, as well. Socrates' answer was characteristically unexpected. While acknowledging the tale had many versions, suggesting it to have been contrived, Socrates also asserted that proving all the ancient stories to have been false was a task reserved only for those inclined to invest a great deal of energy and time to the endeavor.

"I have no time for such things; and the reason, my friend, is this. I am still unable, as the Delphic inscription orders, to know myself; and it really seems to me ridiculous to look into other things before I have understood that. That is why I do not concern myself with them. "

Naturally, Socrates and his protege just vanished into the aether as quickly as they materialized before us. That one comment, translated roughly from the Attic dialect, was naturally noncommittal.

So far, we've embarked on nearly 100 excursions into the upper celestial reaches since the Remote Planetarium started in late March 2020. We've encountered silly kings, fearsome monsters, intrepid heroes, malevolent sirens, ageless gods, and even the primordial chaos itself. However, to come upon an ancient philosopher roaming about the empyreal heights seems far too outlandish. Let's hope it doesn't happen again.

*The historical, not mythological, Cephalus. He was also the father of philosopher Polemarchus who, like Socrates, also ended up being executed by being forced to drink hemlock.

THE SOUTHWORTH PLANETARIUM

70 Falmouth Street Portland, Maine 04103

43.6667° N 70.2667° W

Altitude: 10 feet below sea level

Founded January 1970

Julian Date: 24591158.16

2020-2021: XXXIX

THE DAILY ASTRONOMER

Wednesday, November 4, 2020

Remote Planetarium 117: "Weighing" the Galaxies II

Yesterday we learned how astronomers measured the Milky Way Galaxy's mass by measuring the velocities of stars within it. The greater the stellar velocities, the greater the mass of the host galaxy. Today we address another issue: how can astronomers measure the mass of entire galaxy clusters, which often weigh in at hundreds or thousands of trillions of times more massive than the Sun? That seems like quite a tall order. Fortunately, astronomers generally employ three different techniques for estimating these masses. These are generally used in combination as opposed to being employed individually.

RED SHIFT:

We recall from Monday the technique by which astronomers can measure galactic distances. When a galaxy moves away from us, the light it emits is elongated: its wavelength is increased and shifts toward the red end of the spectrum. When a galaxy moves toward us, its light is compressed: the wavelength decreases and shifts toward the blue end of the spectrum. Astronomers can observe the outer galaxies of the clusters to determine how the cluster's gravitational influence affects the outer galaxy's motion. If a galaxy is between us and the cluster, its red shift will increase due to the cluster's pull on it. The greater the redshift increase, the greater the mass. Also, if a galaxy is on the other side of the cluster, it will experience a pull toward our direction that will dampen the redshift resulting from the Universal expansion.

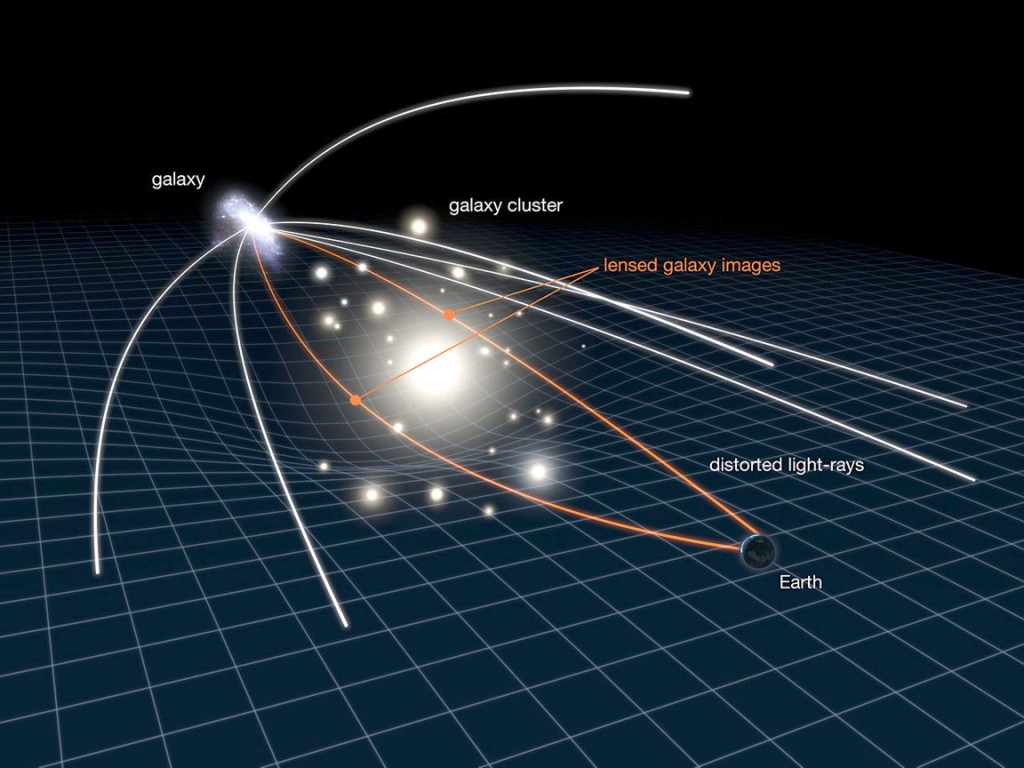

GRAVITATIONAL LENSING:

Imagine an extremely distant luminous object. The light it sends toward us experiences a "lensing" effect as it is focused by the spacetime curvature around a galaxy cluster located between the distant object and Earth. The lensing effect can prove subtle or quite dramatic, depending on the amount of material within the galaxy cluster. By measuring the extent to which the more distant light is distorted through lensing, astronomers can estimate the intervening galaxy cluster's mass.

THE SUNYAEV-ZEL'DOVICH EFFECT:

The Universe is pervaded by the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation. This is the residual radiation left over from the Big Bang event. This radiation is a type of light that has a peak in the microwave region of the electromagnetic spectrum, hence the name. When this light passes through the hot gases within a galaxy cluster, it experiences a shift called the Sunyaev-Zel'dovich effect. In effect, the high energy electrons with the galaxy cluster impart a boost onto the low energy background radiation photons. Astronomers can relate the degree of this shift to the cluster's mass because the greater the high energy electrons, the greater the amount of hot gas present in the cluster which is proportional to the mass.

These methods yield more accurate results when they are employed in conjunction with each other. They have enabled astronomers to "weigh" something as hefty as galaxy clusters.

To subscribe or unsubscribe from the Daily Astronomer: