Julian Date: 2459053.16

2019-2020: CLXXXII

THE DAILY ASTRONOMER

Wednesday, July 22, 2020

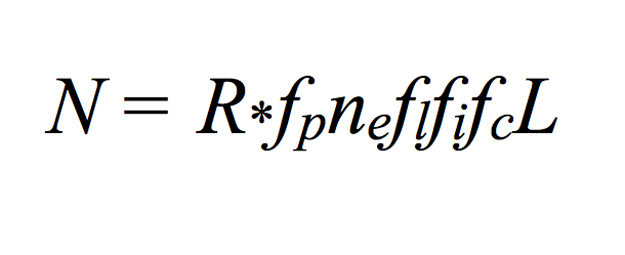

Remote Planetarium 69: The Drake Equation

So, now we ask a question: how many advanced races exist in the Milky Way Galaxy? We recognize that we are at something of a disadvantage when addressing this issue because we know of only one life bearing planet and we're living on it. The importance of asking this question pertains to the search for extraterrestrial life. If life is exceedingly rare so that a given spiral galaxy like the Milky Way might only harbor a few life-bearing worlds, we shouldn't expect to detect any life at all, at least not with the methods currently available to us. However, if life is so common that millions or even hundreds of millions of life- bearing worlds are scattered throughout the galaxy, we should find a trace of at least one of them before long. Yet, how can we begin to take a census of the Milky Way's advanced races?

We can't.

However, we can try to estimate the number through use of the "Drake Equation," a mathematical marvel that combines science and speculation. It was formulated by radio astronomy pioneer Frank Drake (1930 - ) who has been searching for extraterrestrial signals for many decades.

If you're feeling a bit uneasy, don't be. The aim of today's lesson is to work through the Drake Equation piece by piece.

N = number of advanced civilizations in the Milky Way Galaxy

This is the quantity we're trying to determine with all these values. As we shall see, N can vary widely from person to person, depending on their assumptions about some of the factors within the equation. We know that the minimum value of N is 1 because of Earth. Of course, some might insist that based on human behavior the minimum could be zero. Well, bah humbug to that bunch.

R = rate of star formation in the galaxy

According to recent estimates, about three solar masses of material are converted into stars each year. That material is not necessarily transformed into three stars. Remember that most stars are less massive than the Sun. This matter could be turned into as many as seven or eight stars. Or, perhaps, just one star more massive than the Sun. Also, statistics is a tricky business. Some years will experience more star formation than others. We remember also that star formation requires millions of years. By star formation, we refer to the point at which the star becomes active by thermonuclear fusion reactions.

fp = fraction of stars with planets

Based on what astronomers have discovered so far, we can assume that many stars have planets. Analysis of the Kepler Space Telescope findings shows that one in six stars has an Earth-sized planet in a tight orbit. About twenty percent have a "Super Earth" in orbit around them. (A Super Earth is one that is more massive than Earth but considerably less massive than gas giant planets.)

ne = number of planets within a star's "ecoshell" or habitable zone

Astronomers estimate that 40 billion worlds within the Milky Way Galaxy are likely revolving within the habitable zones of their parent stars. Eleven billion of these might be orbiting Sun-like (G type) stars. These estimates are all based on the Kepler Space Telescope findings. Data collected from future missions might induce astronomers to modify these estimates to some extent.

fl = fraction of those planets on which life develops

Now we've careened headlong into the realm of speculation. Unfortunately, the data point available in our own solar system. As we learned earlier this week, Venus, Earth and Mars are all within the Sun's habitable zones. However, Earth alone contains life. That gives us a 1:2 ratio of life-bearing worlds to non-life bearing words in the solar system. Were that ratio to apply to other solar systems, we could assert that life proliferates throughout the galaxy. Our estimate becomes even more optimistic if we find conclusive evidence that life actually did develop on Mars early in its history. That discovery would support the notion that life arises quickly when conditions are conducive to its inception. Of course, it would also suggest that life can be readily snuffed out, as well.

fi = fraction of living species that develops intelligence

Now we're truly limited. Based on our solar system, the rate of intelligent life developing on a life-bearing world is one hundred percent. A beautiful 1/1 fraction. Approximately 3.7 billion years ago, the first traces of primordial life developed on the young, toxic Earth. Now, we're in the age of space stations and 5 G networks. This fraction will remain wholly unknown, unless, of course, some alien emissaries visit Earth and present us with a comprehensive list of life-bearing worlds and intelligent life-bearing worlds. On the other hand, if we accept that microbial life did arise on Mars before it was eradicated, then this fraction becomes 1/2. Both fractions, however, are predicated only on our own solar system and therefore might not be indicative of the galaxy in general.

fc = fraction releasing detectable signals into space

Well, we know we did, although we needed 3.7 billion years to develop the capability. During that immense amount of time, Earth sustained asteroid bombardments and snowball Earth epochs, to name just two of the perils life has confronted over the course of Earth's natural history. The greatest mass extinction, the Permian-triassic event, occurred 250 million years ago. That mass extinction devastated 96 percent of all ocean species and a majority of the other life forms, as well. Earth life literally required millions of years to recover from that extinction event. It is possible that life on other worlds was completely destroyed by some great extinction. We just know that life on Earth survived.

L = length of time releasing detectable signals

Two ways to approach this last value. First, radio was invented in the late 19th century. By the 1940's humans developed atomic bomb technology. Not much later the nuclear stockpile we amassed was so large it could have wiped out Earth life ten times over. Humans were transmitting signals for slightly more than half a century before they were at risk of self-annihilation. Secondly, many modern radio signals don't propagate like the original waves did. Many of today's broadcasts are not broadcasting into space anymore. Even if the outer space broadcasting ended altogether today, humans have been transmitting detectable signals for more than a century. Again, Earth is our only data point and might not be representative of other life-bearing planets, if they exist in the first place.

The Drake Equation is not intended to settle the issue of how many advanced civilizations exist in the galaxy. Instead, it provides us with a method by which to estimate that number: one that will likely remain unknown for an immensely long time.

To subscribe or unsubscribe from the Daily Astronomer: