Atlas: The Sky Holder

Long before the Trojan War, another ten year long conflict nearly devastated Heaven and Earth. This fierce war was the Titanomachy, the battle pitting the Titans, an older generation of gods, against the younger Olympians. This war began after Zeus, the greatest of the gods, freed his siblings from the stomach of Cronos, the Titan who sired them. Fearing that his position would be usurped by his children as he had overthrown his father Uranus, Cronos had tried to swallow every one of his offspring as soon as Rhea gave birth to them. He consumed them all except Zeus, whom Rhea concealed after delivery. She presented Cronos with rocks enshrouded in swaddling clothes in Zeus' stead. Zeus grew to maturity in three days under the care of Amalthea, the goat maiden, who nourished him on nectar and ambrosia. Once grown, Zeus and his mother Rhea conspired to liberate the others. They tricked Cronos into ingesting an emetic and he regurgitated the other Olympians. There followed a decade-long fight for dominion over the Universe. The Olympians ultimately prevailed and showed no mercy to the vanquished Titans. Most were consigned to Tartarus, the punitive region of the Underworld where the most wicked souls suffered inelcutable torments. Atlas, a titan who fought valiantly against the gods, was spared this fate. Instead, Zeus condemned him to an eternity at Gaia's western edge where he was forced to hoist up the sky. Contrary to popular belief, Atlas did not hold the world on his shoulders. Instead, the weight of the celestial spheres was his true burden. Although Atlas was never a prominent mythological figure, he did play an important role in Hercules' eleventh labor. During this labor, King Eurystheus required Hercules to bring him three of Hera's golden apples that were protected in the Garden of the Hesperides. While Hercules didn't know the garden's location, he did know that Atlas had fathered the Hesperides and would know how to find them. He approached Atlas and asked for his assistance. Atlas agreed to fetch the apples, himself, if Hercules would consent to hold up the heavens in his absence. Hercules happily shouldered the heavens while Atlas ran swiftly to his daughter's garden. Atlas returned days later and showed Hercules the three golden apples. "Excellent!" Hercules exclaimed. "Here, you may now hold up the heavens again." Atlas declined. "No, my friend, I shall not. Having been freed from my burden, I am loath to shoulder it again. I will deliver these apples to your king and you may spend eternity hoisting the spheres aloft." Instead of appearing angry, Hercules seemed glad. He smiled broadly at Atlas. "You don't know what a relief it is to me to take the heavens from you. By doing so, I shall no longer be required to perform these horrible labors. Each one has been far more dangerous and onerous than the one before it. After this labor, only one other remained: one that I knew would have destroyed me. By making me remain here, you have gifted me with immortality. Take the apples with my gratitude. But first, one small favour. The weight has caused a pain in my shoulder. Please take the heavens for just a moment so I can place some padding on it." After Atlas hoisted the heavens back on his shoulder, Hercules took the apples and fled, much to Atlas' chagrin.

In another story, this one told by Ovid, Perseus alleviated Atlas' burden by showing him Medusa's head. Atlas was then petrified and became the Atlas mountain. Most mythographers now discount that story as Perseus was Hercules' great grandfather and had died long before the twelve famous labors.

THE SOUTHWORTH PLANETARIUM

207-780-4249 www.usm.maine.edu/planet

70 Falmouth Street Portland, Maine 04103

43.6667° N 70.2667° W

Altitude: 10 feet below sea level

Founded January 1970

Julian Date: 245960.16

Julian Date: 245960.16

2019-2020: CXXX

THE DAILY ASTRONOMER

Tuesday, April 21, 2020

Remote Planetarium 17: The Constellations

Why have we retained the constellations? After all, they are the merest contrivances: configurations of stars that generally lack any true association. Modern day astronomers would no more acknowledge the constellations as legitimate than they would consult a horoscope. Why do they remain? Simple. Because we want them to remain. Humans, being prodigious creators, naturally want beautiful artistic works to adorn the world and the sky above it. Does anybody think that since we all have desk calendars, we should dismantle Stonehenge and pave over Salisbury Plain? Should we take a paint roller to the Sistine Chapel ceiling? Who wants a gray world devoid of creative brilliancy?

We want the constellation and they're here, or, at least, up there!

Whenever people discuss the origin of the constellations, they generally claim that the stars have always exercised a fascination over humans owing to their remoteness. That could very well be. Unfortunately, all of our assumptions about our remote ancestors are a meager mix of inference and speculation.

We do know that the night sky contains 88 distinct constellations: those classified by the International Astronomical Union. They are Andromeda, Antlia, Apus, Aquarius, Aquila, Ara, Aries, Auriga, Bootes, Caelum, Camelopardalis, Cancer, Canes Venatici, Canis Major, Canis Minor, Capricornus, Carina, Cassiopeia, Centaurus, Cepheus, Cetus, Chamaeleon, Circinus, Columba, Coma Berenices, Corona Austrina, Corona Borealis, Corvus, Crater, Crux, Cygnus, Delphinus, Dorado, Draco, Equuleus, Eridanus, Fornax, Gemini, Grus, Hercules, Horologium, Hydra, Hydrus, Indus, Lacerta, Leo, Leo Minor, Lepus, Libra, Lupus, Lynx, Lyra, Mensa Microscopium, Monoceros, Musca, Norma, Octans, Ophiuchus, Orion, Pavo, Pegasus, Perseus, Phoenix, Pictor, Pisces, Piscis Austrinus, Puppis, Pyxis, Reticulum, Sagitta, Sagittarius, Scorpius, Sculptor, Scutum, Serpens, Sextans, Taurus, Telescopium, Triangulum, Triangulum Australe, Tucana, Ursa Major, Ursa Minor, Vela, Virgo, Volans and Vulpecula.

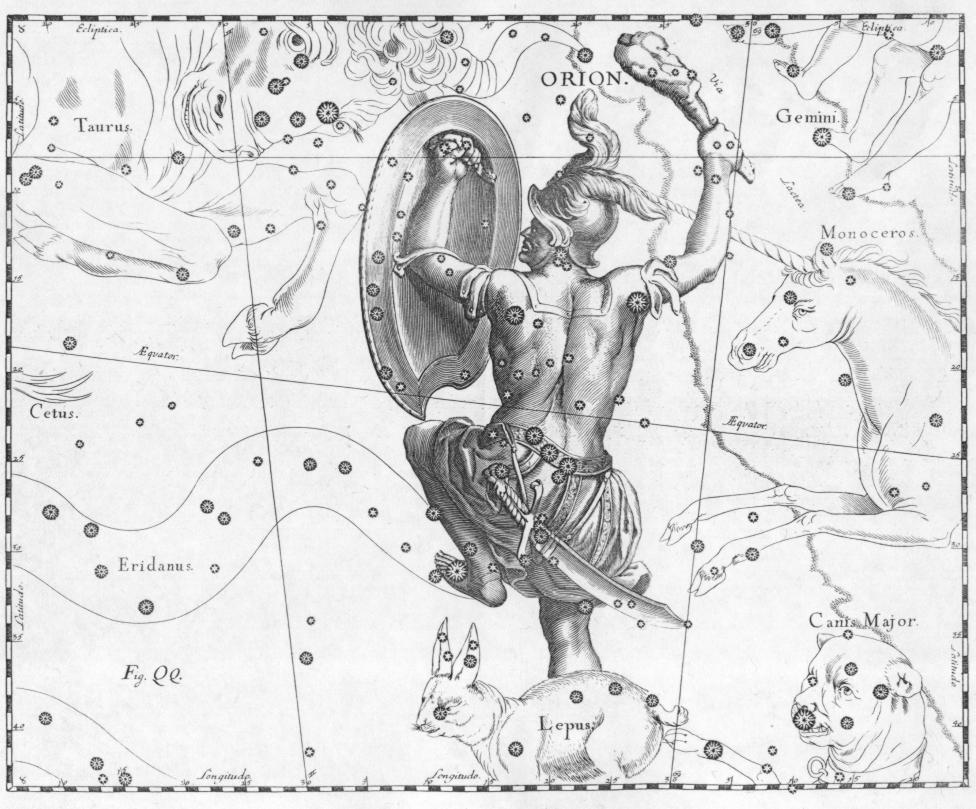

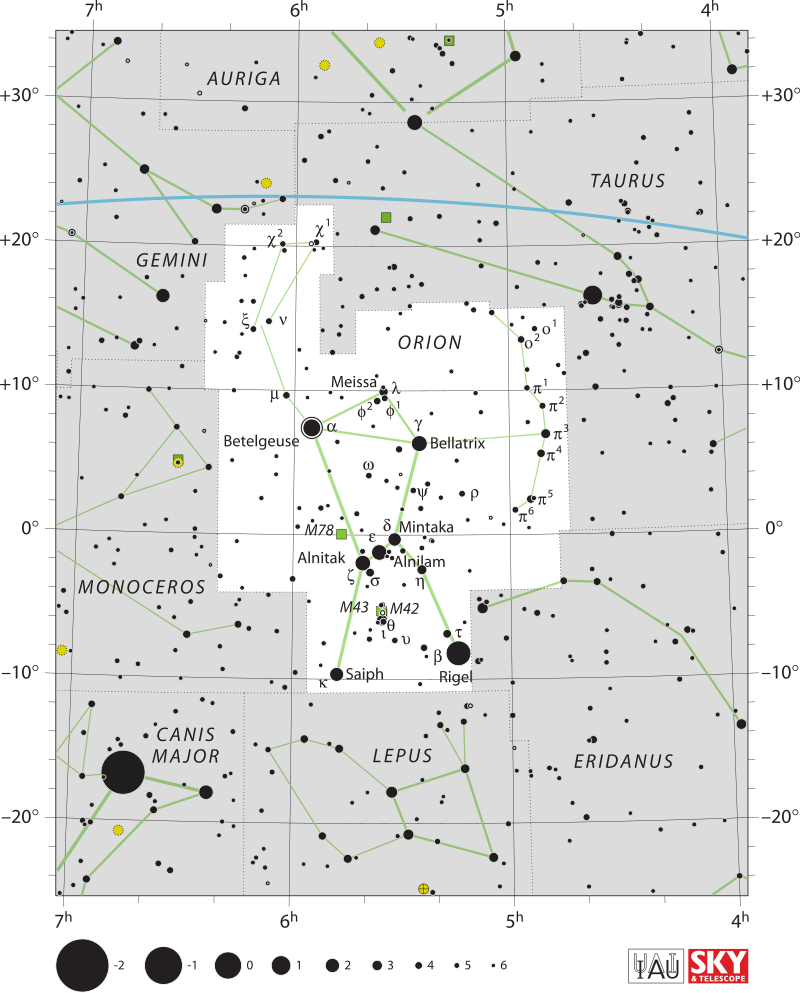

In 1928, the IAU developed a formal listing of these constellations including the boundaries surrounding all of them. The image below shows the entire Orion the Hunter region colored white. Each of the 88 regions along the celestial sphere are defined by an associated constellation.

The IAU boundaries were set by Belgian astronomer Eugene Joseph Delporte (1882-1955). His work augmented that of American astronomer Henry Norris Russell (1877-1957), of HR Diagram fame (we'll get to that topic later.) Although Russell's list was comprehensive, it lacked the demarcations the IAU needed to establish their tyrannical dominion over the sky,

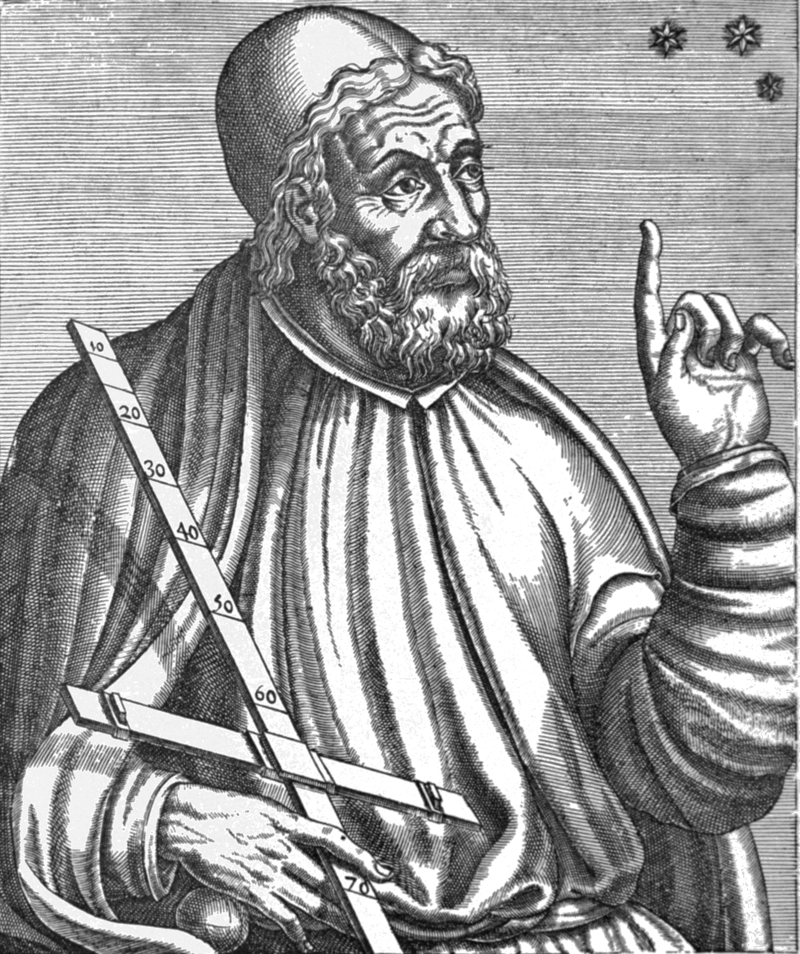

More than half of these eighty eight constellations were based on those compiled by Claudius Ptolemy (AD 100 - 170). He listed these forty eight in books VII and VIII of his famous work the Almagest

While his list was primarily a compilation of constellations derived from Hellenistic tradition, they were based on ancient sources: such as Sumerian and Babylonian folklore. All the prominent constellations such as Orion, Pegasus and Perseus are part of "Ptolemy's 48." So, too, are all the constellations comprising the Zodiac:

Pisces, Aries, Taurus, Gemini, Cancer, Leo, Virgo, Libra, Scorpius, Ophiuchus, Sagittarius, Capricornus and Aquarius.

We can ascribe the remaining constellations to three other people:

- Petrus Plancius (1552-1622)

- Johannes Hevelius (1611-1687)

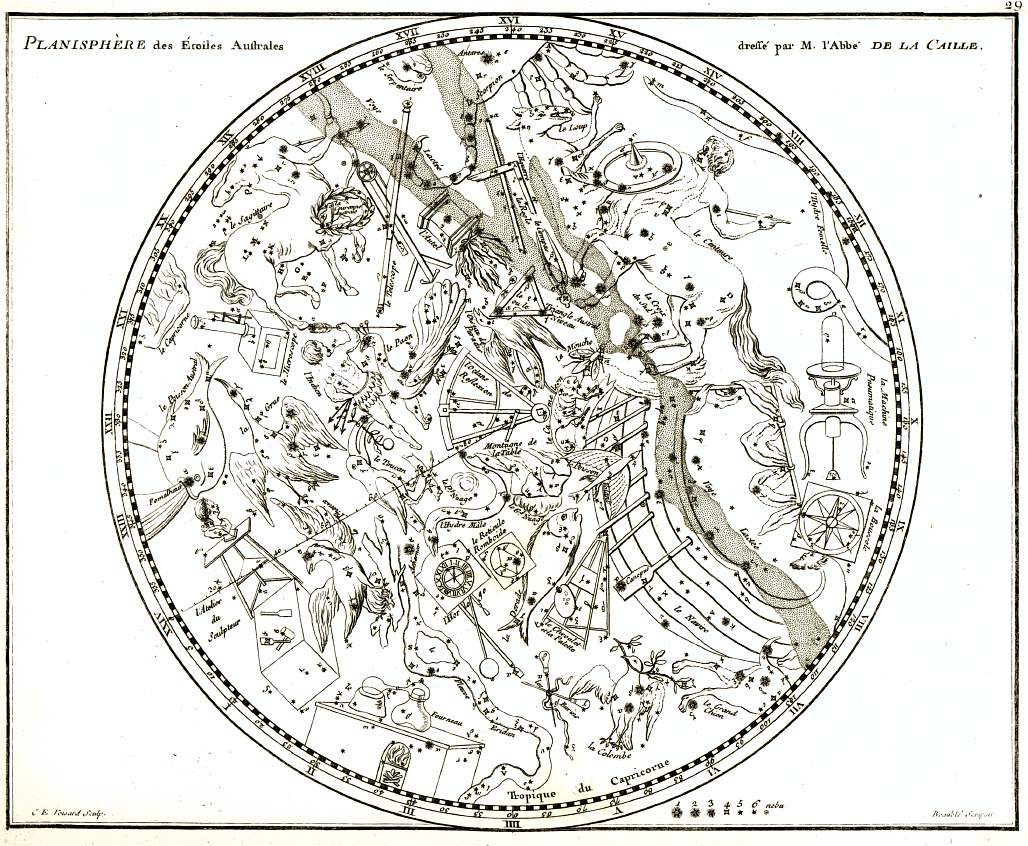

- Nicholas -Louis de Lacaille (1713-1762)

Plancius gave us many of the southern constellations such as Dorado, Tucana and Triangulum Australe, which are the Swordfish, Tucan and Southern Triangle, respectively.

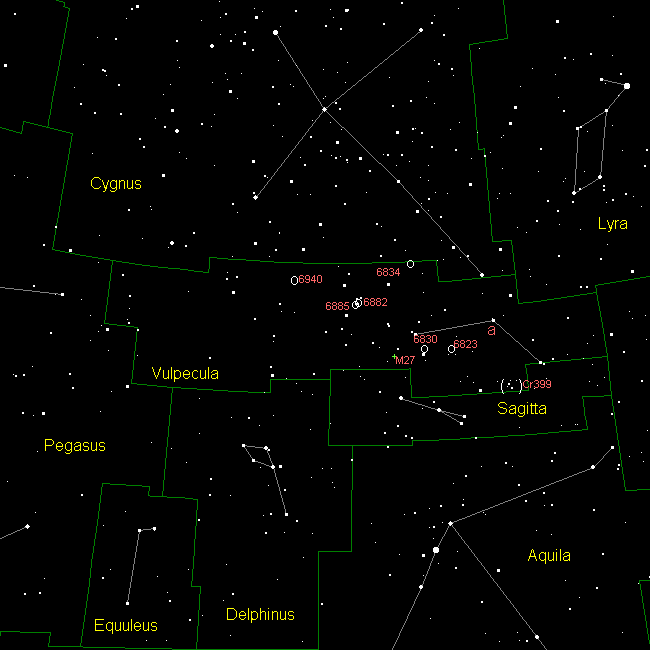

Hevelius "filled in" many darker regions within the northern sky. He developed seven of the IAU's 88 constellations, all of them minor: Canes Venatici, Lacerta, Leo Minor, Lynx, Scutum, Sextans and Vulpecula.

Vulpecula the Fox: one of the seven official constellations developed by Johannes Hevelius.

Nicholas-Louis de Lacaille provided the final additions to the current constellation map. These were also southern constellations, including Mensa, Telescopium and Octans, meaning table, telescope (yes, we know you figured that out) and Octant, an old navigational instrument. Octans is the southernmost constellation and contains Sigma Octantis, the southern hemisphere's equivalent to Polaris. Sigma Octantis is quite faint (magnitude 5.4) and about a degree away from the south celestial pole.

LaCaille's planisphere containing the constellations he personally crafted in the

18th century.

While this article offered only a cursory introduction to constellation history, we hope it will lend insight into the development of the constellations that loom above us every night.

To subscribe or unsubscribe from the Daily Astronomer: