Persephone: Queen of the Doomed

There was a time, quite long ago, when our young world remained perpetually verdant. Water flowed fresh through each river and gushed freely over every waterfall. The crops were forever abundant, the flora luxuriant and all forests were crowned by lush canopies. An enveloping warmth pervaded a land that never knew the faintest insinuation of winter chill. It was into this world that Zeus and Demeter, goddess of harvest, brought forth their only daughter, Persephone. Like all those divinely conceived, Persephone grew rapidly to maturity. By virtue of her enchanting beauty, she was pursued by many suitors. By virtue of her free spirit, she eluded them all. Hers was a joyous life devoted to running, playing and flower gathering with her mother through every glade, meadow and moss coated woodland. Though she was constantly chased, she remained cheerfully chaste. Life was so exquisitely blissful that she could not bear the notion of being clasped in double harness with any man. Of course, Persephone didn't know that Hades, god the gloomy underworld to which the souls of the dead are consigned, had coveted her from afar. In desperation Hades finally spoke to his brother Zeus of the intense passion he developed for his niece. Zeus sympathized, as he, himself, was prone to experience such lusts from time to time (to time to time to time). When Hades suggested that there was nothing else for it but to spirit Persephone away to the underworld, Zeus said nothing. Hades interpreted the silence as a tacit approval of his intentions. One afternoon, while Persephone was gathering anemone ("windflowers") as her mother was elsewhere, a great chasm split open in the meadow. From it emerged Hades riding a chariot guided by four midnight black steads. Persephone started to flee, but was promptly captured. Before she could call out to her mother, Persephone, Hades and his chariot dove into the chasm which closed firmly behind them. A while later Demeter actually trod over that sealed fissure while searching for her daughter. She called out repeatedly, only to hear nothing. Her concern grew into alarm as the rest of the day passed with no sign of her daughter. She devoted the next nine days to searching for Persphone. During this time, she didn't eat, drink or sleep. She searched every crevice and hollow for Persephone, but to no avail. She ascended to Olympus and asked Zeus if he knew of their daughter's whereabouts. He feigned ignorance and tried to assure Demeter that she had no cause for anxiety. Demeter then consulted Helius, god of the Sun. From his vantage point, he saw all that transpired on Earth. He told Demeter that Hades had kidnapped her daughter and brought her into the after realm. He also suggested that Zeus, himself, might have been complicit in the abduction. He did admit that he based that assumption on inference rather than observation. Distraught and furious, Demeter disguised herself as a mortal and roamed the world for a year. In this guise, she deprived everything she touched of vitality: crops withered, grasslands and forests alike perished and a deep chill pervaded the land. Humans were starting to die of starvation in such numbers that Zeus, himself, intervened. He and the other Olympians tried in vain to persuade Demeter to return to Olympus and rejuvenate the land back to its previous fecundity. Demeter stubbornly refused to do so until her daughter returned. Fearing the onset of a global famine, Zeus ordered Hades to relinquish Persephone back to her mother. Knowing his brother to be the far more powerful of the two, Hades yielded. He summoned Persephone forth and told her she was returning to the upper world. For the first time since her arrival, she smiled. Persephone had been inconsolably miserable since the abduction. She had spent her time housed in a bed chamber, often looking forlornly through the window at the fog enshrouded gloom beyond it. As she had taken no food during her time there, Persephone was ravenously hungry when Hades announced her release. Hades offered her some pomegranates, saying they were an offering of contrition. Persephone took four and devoured them. Hades then explained that by eating that fruit, Persephone was eternally bound to the Underworld. She was then desolate, having come so close to liberation only to be imprisoned forever by her own actions. However, Rhea, Zeus' titaness mother, pitied Persehone. Having also been the Earth mother's eldest daughter, Rhea felt such a deep affinity for Demeter and her daughter that she brokered a compromise. Persephone could return to the sunlit upperworld for eight months each year. The other four months -one for each consumed pomegranate- she would be required to live with Hades. When Persephone ascended each year, Demeter was gladdened. The world became warm. The crops and all the flora on it flourished. During the four months Persephone lived with Hades, Demeter was so distraught that the crops perished, the fields withered and the land grew cold and barren. Ever since Rhea arranged this compromise, the world was perpetually verdant no longer, but instead experienced the alterations we now call seasons. Persephone has been identified with the constellation Virgo the maiden, the largest of the zodiac patterns. Virgo rises after sunset in March, heralding spring's return. Virgo then sets with the Sun in September, indicating that autumn's arrival is imminent.

THE SOUTHWORTH PLANETARIUM

207-780-4249 www.usm.maine.edu/planet

70 Falmouth Street Portland, Maine 04103

43.6667° N 70.2667° W

Altitude: 10 feet below sea level

Founded January 1970

Julian Date: 245959.16

Julian Date: 245959.16

2019-2020: CXXIX

THE DAILY ASTRONOMER

Monday, April 20, 2020

Monday, April 20, 2020

Remote Planetarium 16: Maps and Magnitudes

Good morning!

This week starts with star charts (or star maps, if you prefer.)

We'll learn the basics of understanding them and the symbols printed on them.

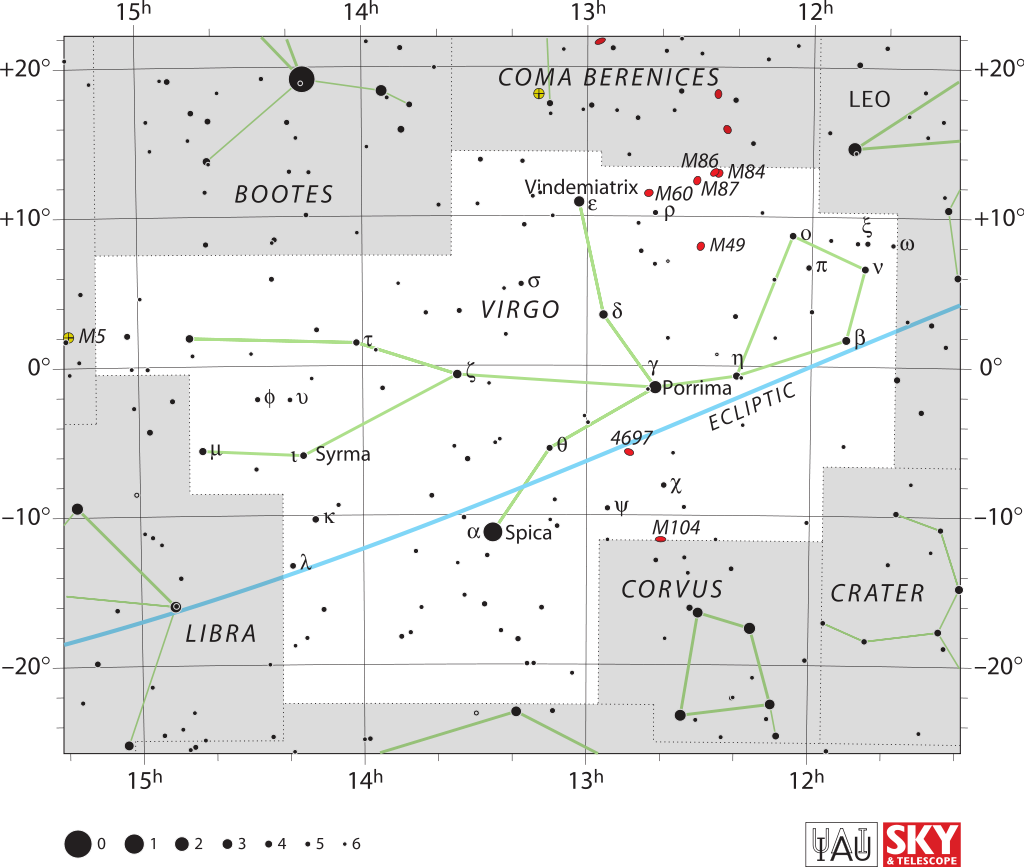

Regard the following star chart segment centered on the constellation Virgo.

It looks like an indecipherable mish-mash of symbols, numbers and constructs. Small wonder that Walt Whitman stormed outside in a huff. However, please bear with us as we work through it.

- Along the top we see 15h 14h 13h 12h. Those are right ascension markers. Recall last week we learned that right ascension measures a celestial object's angular distance from the vernal equinox. The right ascension scale extends from 0 - 24 hours, both of which denote the vernal equinox point. It is the celestial equivalent to longitude.

- Along the sides we see degree marking denoting declination. Declination measures a celestial object's angular distance north or south of the celestial equator. The 0 degree declination line represents the celestial equator.

- The blue arc represents the "ecliptic," the sun's annual apparent path through the sky. Notice toward the right side the ecliptic intersects the celestial equator. That intersection, which corresponds to 12 hours right ascension, is the autumnal equinox: the Sun's position on the first day of autumn.

- The white area surrounding Virgo defines the "Virgo region." Any celestial object observed within this region is said to be "in Virgo."

- The M objects within Virgo, such as M49 and M60 are "Messier objects, named for French astronomer Charles Messier (1730-1817) an avid comet hunter who, ironically, is best known for having compiled a catalog of celestial objects that resemble comets, but aren't. We still refer to this compilation as the "Messier Catalog,"and the bodies listed within it are known as "Messier objects." M49 and M60 are both elliptical galaxies approximately 56 million and 57 million light years distant, respectively. We will encounter Messier objects and galaxies many times during this course.

- The Greek letters seen by some of the stars are part of the Bayer Nomenclature System developed by German astronomer Johann Bayer (1572-1625). In Bayer's "Uranometria." This scheme assigns the letter alpha to the constellation's brightest star, beta to the second brightest, gamma to the third brightest, et cetera. A star within the constellation would be named using this Greek letter followed by the Latin genitive of the host constellation name. For instance, Spica, Virgo's brightest star, is designated Alpha Virginis.

MAGNITUDES

The concept of "magnitude" is actually quite straightforward. It is the system astronomers use to measure the brightness of celestial objects: stars, planets, the Moon, even comets, asteroids and meteor trails. If it's in the sky and exudes light, either self-generated or reflected, it has a magnitude value. As we shall discover throughout the course, this system is both useful as a categorizing tool and as a means of discerning stellar distances.

Historians credit the magnitude system's invention to Nicean astronomer Hipparchus (190 - 120 BCE*) His was the first catalog to include a six-category scheme indicating stellar brightness. He assigned the brightest stars the designation "magnitude 1." He labeled the faintest stars visible as "magnitude 6." He consigned the remaining stars to the four intervening categories based on their relative brightness. As each category was not calibrated to reflect variations within each one, Hipparchus' scheme was quite imprecise. Yet, it became the foundation on which the modern magnitude system was based.

The concept of "magnitude" is actually quite straightforward. It is the system astronomers use to measure the brightness of celestial objects: stars, planets, the Moon, even comets, asteroids and meteor trails. If it's in the sky and exudes light, either self-generated or reflected, it has a magnitude value. As we shall discover throughout the course, this system is both useful as a categorizing tool and as a means of discerning stellar distances.

Historians credit the magnitude system's invention to Nicean astronomer Hipparchus (190 - 120 BCE*) His was the first catalog to include a six-category scheme indicating stellar brightness. He assigned the brightest stars the designation "magnitude 1." He labeled the faintest stars visible as "magnitude 6." He consigned the remaining stars to the four intervening categories based on their relative brightness. As each category was not calibrated to reflect variations within each one, Hipparchus' scheme was quite imprecise. Yet, it became the foundation on which the modern magnitude system was based.

British astronomer Norman Robert Pogson (1829 - 1891) formulated the magnitude system astronomers still use today. He introduced into this system a value known as the "Pogson ratio," which is 2.512. A star measuring magnitude 1.0 is 2.512 times brighter than a star of magnitude 2 which, itself, is 2.512 times brighter than a magnitude 3 star. Pogson selected this ratio because it is the fifth root of 100, so a magnitude 1 star is precisely 100 times brighter than a magnitude 6 star.

Apart from quantifying the system, Pogson also expanded its parameters to accommodate those objects that are far brighter than those stars previously denoted as magnitude 1 and those objects dimmer than magnitude 6. Today, the magnitude system extends from the Sun (magnitude -26.7) to the faintest celestial objects that the Hubble Space Telescope has observed (magnitude + 27) As examples, Sirius, the brightest night sky star, is magnitude -1.46; Venus, at maximum brightness, is magnitude -5.0.

Spica's magnitude is 0.97, making it the sky's 16th brightest star.

One important note: The International Astronomical Union has designated eighty eight different constellations. In thirty-three of them, the "alpha" star is not the brightest.

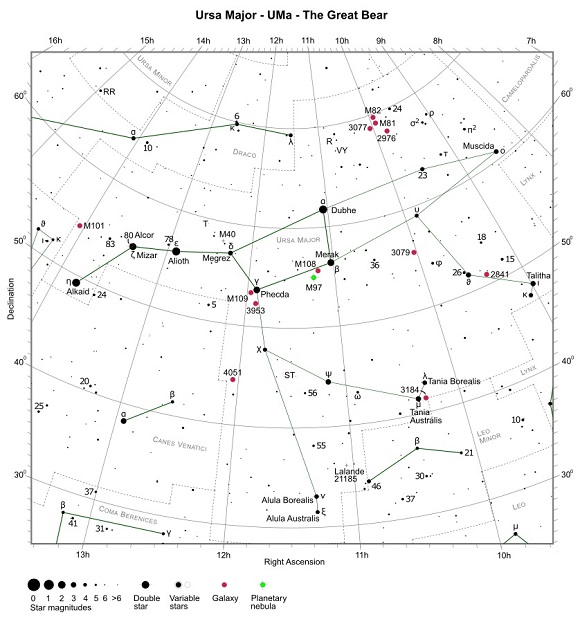

We conclude with this star chart centered on Ursa Major. We again observe the constellation boundaries, right ascension, declination markers, the Bayer system Greek letters, and the Messier objects. Included on this chart - and absent on the previous one- are Flamsteed numbers, named for Johann Flamsteed (1646-1719), the first Astronomer Royal. His system assigns numbers to each constellation according to their position relative to the vernal equinox. In other words, by increasing right ascension.

Tomorrow, we move from star charts to the a brief history of the constellations.

To subscribe or unsubscribe from the Daily Astronomer: