Oedipus Rex

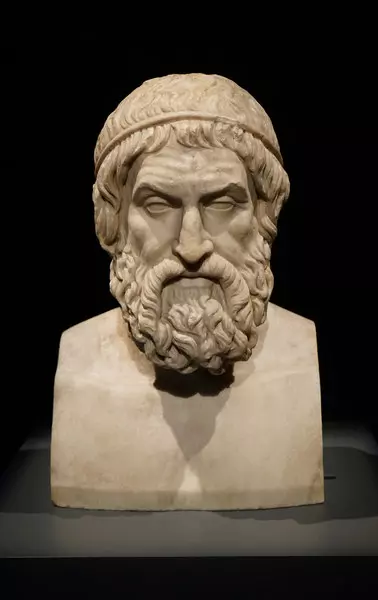

Even people who care little about classical mythology have likely heard the name "Oedipus." We can attribute his enduring fame largely to Sigmund Freud who unnerved the entire male populace with the psychoanalytic theory the "Oedipus Complex," also known as the "Oedipus Conflict." We'll cheerfully avoid any explanation of this disquieting concept and proceed immediately to the disturbing tale involving this most tragic of mythological figures. Laius, king of Thebes, was married to Jocasta, a distant relation. Theirs was a happy, though not particularly fruitful, marriage. It was only after the passage of many years that Jocasta finally gave birth to their first child. Their son's arrival engendered morbid fear in his father for he had heard a Delphic oracle warning him that his son would eventually kill him and marry Jocasta. Hoping to confound the prophecy, Laius punctured the baby's foot with a nail and ordered a servant to expose him on a mountainside. It was in this manner that parents dispatched an unwanted child while not actually committing outright murder. A shepherd found the exposed baby soon after its abandonment and brought him to Corinth. He presented the baby to Polybus, the Corinthian King. This king, who was childless, decided to raise the infant, himself. He named the child "Oedipus," meaning "swollen foot." Polybus, his wife Merope -not the Pleiad Merope-and Oedipus lived happily and prosperously. Oedipus deeply loved the two people he presumed to have been his parents. Neither Polybus nor Merope had ever told Oedipus of his adoption. One day at a banquet a drunken Corinthian noble taunted Oedipus, then a young adult, about his appearance. "You look nothing like King Polybus," he sneered. "Nor your mother, neither!" Oedipus responded to this teasing with his fists, hurting his tormentor grievously. Oedipus was both quick tempered and preternaturally strong. Insults that articulate one's own thoughts often prove to be the most effective. Oedipus had long been troubled by the lack of resemblance between him and Polybus. After this scuffle, he traveled to Delphi to ask the Sibyl about his parentage. As soon as he arrived, the Sibyl spat at him. "Be gone! You shall kill your father and marry your mother! You befoul the very air about you! Be gone!" Horrified, Oedpius ran from Delphi and resolved to leave Corinth immediately and never return. As he walked from Delphi toward a nearby kingdom of Thebes, he encountered King Laius and four attendants in a chariot at a location where three roads converged. "Out of the way!" Laius commanded him. "We are on a pilgrimage to Delphi and will not be impeded by crippled vagabonds!" (Due to the foot puncture, Oedipus limped and always used a walking stick.) Oedipus angrily suggested that they move their chariot to make way for him. At this Laius struck him with a rod while the chariot drove past. Oedpius responded by killing the king with a single blow. He then rapidly dispatched three of the other attendants. One fled before Oedipus had the chance to kill him. Soon thereafter Oedipus came upon Thebes, but found the gates to have been shut. While trying to find another entrance, he encountered a hideous creature with a woman's face and a lion's body. It was the Sphinx that had been plaguing Thebes for many weeks. She would ask every person she met the same riddle: "What goes on four feet in the morning, two feet at noon, three in the evening and is strongest when on the fewest number of feet?" Nobody had yet solved the riddle and so as a punishment she devoured all those she asked. Crouching menacingly above him, the Sphinx asked Oedipus the riddle. "Simple," he said. "The answer is 'Man.' He crawls on all fours as an infant, walks upright as a young adult and requires a cane in old age." Having always needed a walking stick, Oedipus was keenly aware of his own impediment and so quickly realized the meaning of "three legs." Distraught, the Sphinx committed suicide by hurling herself off a nearby cliff. A sentry observed the encounter and watched as the Sphinx plummeted to her death. He opened the gate and welcomed Oedpius gladly. The sentry then summoned Creon, the queen's brother, who was behaving as regent during his brother's absence. "You have saved Thebes from the terror," Creon said. "We have just learned that our king Laius and his entourage have been slain by robbers. As a reward for your service, you shall be offered the kingship and his widow Jocasta's hand in marriage." Oedpius accepted both eagerly for he had been homeless and deprived of any means. Over the next two decades, Oedipus and his queen Jocasta ruled Thebes well and wisely. They produced four children: Antigone, Ismene, Eteocles and Polynices. Suddenly and inexplicably, a plague laid siege to Thebes. Citizens were dying in the streets. The food supply was halted, causing widespread hunger and misery. Creon traveled to Delphi to learn how they could stop the plague. It was the first time anyone from Thebes had gone to consult the oracle since Laius left twenty years before to seek guidance on how to contend with the Sphinx. When Creon returned he simply said, "To stop the plague we must banish Laius' murderer." Relieved, Oedipus announced that nobody in Thebes was permitted to provide shelter or any other protection to the previous king's killer on pain of death. Oedipus announced that he would spare no effort to identify Laius' murderer and expel him at once. Matters worsened for Oedpius, however, when he called forth the prophet Tiresias for guidance on how to find the murderer after the passage of so many years. Tiresias protested that he did not want to speak and preferred to return home. Thinking that Tiresias was protecting the culprit, Oedipus commanded Tiresias to reveal what he knew or face severe punishment. Tiresias then replied, "You are the murderer you seek!" Oedipus furiously sent Tiresias away and then told his wife Jocasta what the "blind old fool" had said. "Prophets and oracles are worthless," she said scornfully. "My husband Laius was supposed to have been murdered by my son. However, he was killed by robbers as he traveled to Delphi. Our one son had been exposed at birth and died." Nervously Oedipus asked about Laius' death. "When and where did it occur?" Jocasta said, "at the place where the three roads converge just outside of Thebes. He was killed soon before you arrived to save us from the Sphinx." Jocasta further explained that only one of the king's entourage had survived and was living in a remote village. Now alarmed, Oedipus and Jocasta commanded him to be brought forth. When questioned, the man nervously identified Oedipus as Laius' killer. Then an old Corinthian shepherd came forth and explained that he had saved Jocasta's infant from a mountainside and presented him to his king Polybus, who had raised him as though the baby were his own. The horrible truth now revealed, Jocasta ran into the palace and hanged herself. Oedpius punctured his own eyes with a dagger and was expelled from Thebes in the company of his dutiful daughter/sister Antigone. Though miserable and widely reviled, Oedipus eventually found refuge outside of Athens where he was warmly welcomed by Theseus (yes, that Theseus). Even though in later life Oedpius was impoverished and hated, he at least died comforted and at peace.

THE SOUTHWORTH PLANETARIUM

207-780-4249 www.usm.maine.edu/planet

70 Falmouth Street Portland, Maine 04103

43.6667° N 70.2667° W

Altitude: 10 feet below sea level

Founded January 1970

Julian Date: 245969.16

Julian Date: 245969.16

2019-2020: CXXXVII

THE DAILY ASTRONOMER

Thursday, April 30, 2020

Thursday, April 30, 2020

Remote Planetarium 24: Amazing Moons

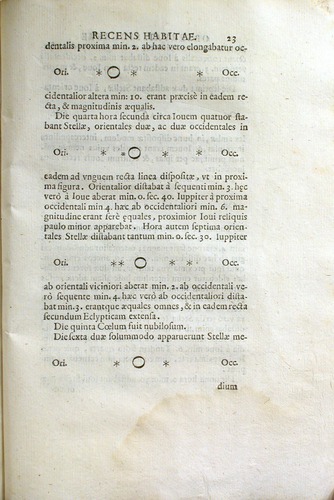

The early 17th century was a dark time for those who insisted that all the other solar system bodies revolved around Earth. First, Johannes Kepler provided a mathematical framework for the planetary motions that placed the Sun firmly in the solar system's center. He wasn't the first, of course. Copernicus shifted Earth from its revered place more than half a century earlier. Secondly, Galileo Galilei had made modifications to a lens system invented by a Dutch mariner named Hans Lippershey. This system, called a "telescope," enabled Galileo to observe the heavenly bodies more closely than ever before. While observing the planet Jupiter through late 1609/early 1610, Galileo observed what he initially believed were three "stars" close to Jupiter. Soon after he discovered another "star," Galileo realized that they were moving in a manner unlike that of any other star. He rightly concluded that these "stars" were actually revolving around Jupiter just as the moon orbits Earth. Galileo collected direct evidence that objects were revolving around a celestial body. This conclusion was the death knell for the geocentric ("Earth centered") solar system model.

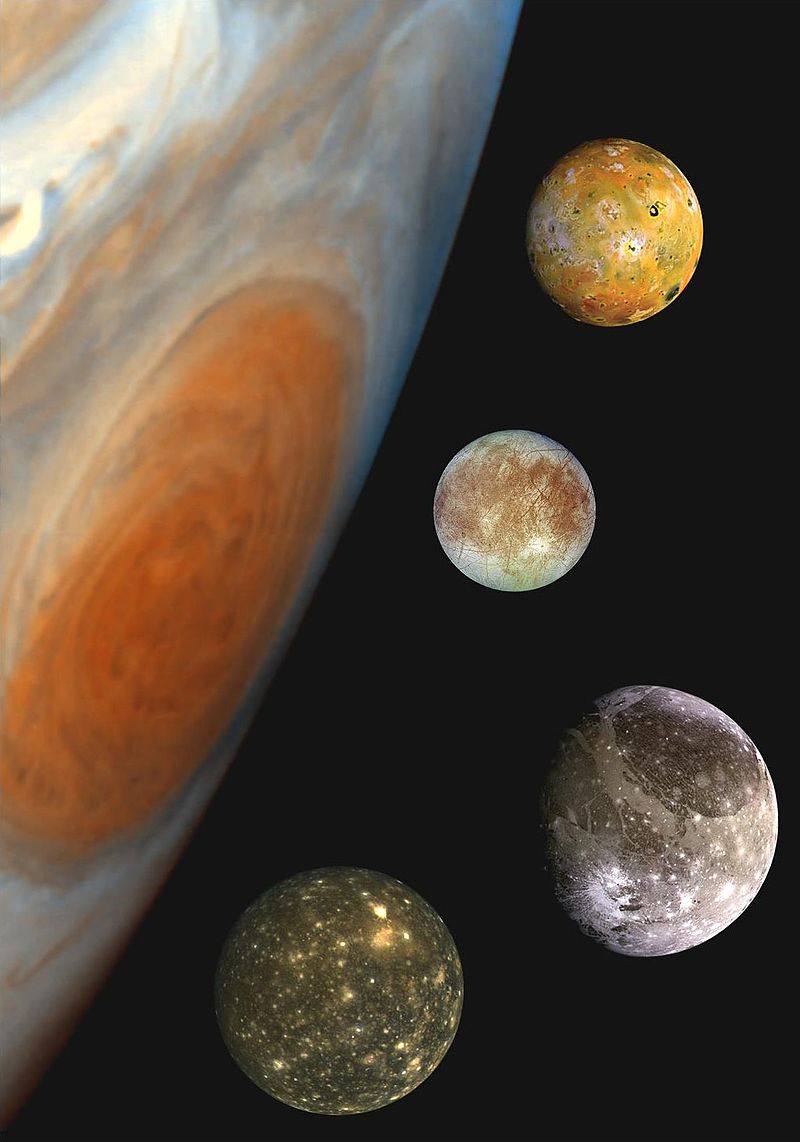

Galileo first recorded his observation of Jupiter's largest satellites in his 1610 publication Siderius Nuncius ("The Starry Messenger") These four Jovian satellites, known now collectively as the "Galilean moons," were the first moons discovered beyond the one revolving around Earth. Named for some of Jupiter's many lovers, they are Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto.

- Ganymede, the solar system's largest moon, is larger than Mercury or Pluto, though it is less dense owing to its icy composition

- Europa, coated entirely by ice, might harbor life within a deep subterranean ocean. Tidal forces exerted between Europa, Io and Jupiter impart sufficient heat energy to maintain a liquid ocean beneath its surface.

- Io is known for its erupting volcanoes. The same tidal stresses that produce Europa's ocean are also responsible for Io's volcanic activity.

- Callisto is the "battered" moon. Craters cover more than 90% of its surface. While all bodies have withstood repeated asteroid impacts, Callisto still shows its scars all over its body.

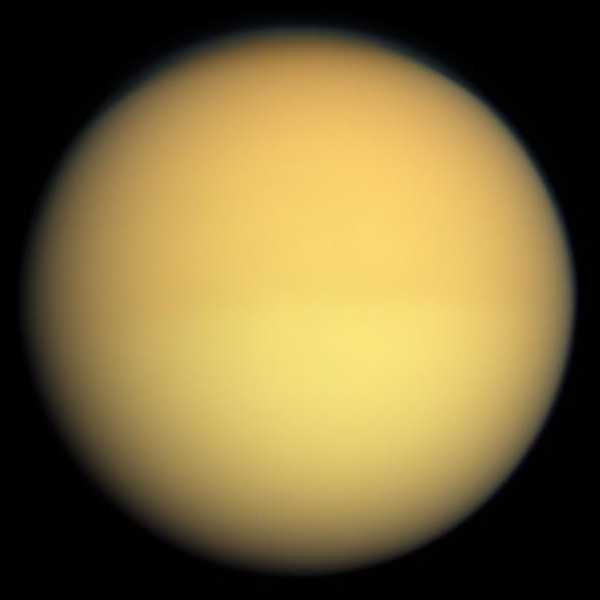

Forty five years elapsed until Christian Huygens (1629-1695) discovered Saturn's largest moon, Titan. Though he announced his discovery in 1655, he didn't officially publish this discovery until 1659, when he included the detection in his 1659 publication Systema Saturnium.

- Titan is the atmospheric planet. It is one of the four moons known to harbor a "collisional atmosphere," meaning that the gas molecules collide with others before traveling an appreciable distance. Titan's atmosphere is thicker than the atmospheres surrounding the other moons. Consisting primarily of nitrogen, methane and hydrogen, Titan's "air" is likely similar to the gas clouds that enshrouded the early Earth

William Herschel discovered Uranus in 1781. Six years later he announced the discovery of two of its moons: Titania and Oberon. Though initially listed as Uranian satellites II and IV, these moons and all the others now known to be revolving around Uranus are named for characters created by either William Shakespeare or Alexander Pope. Herschel also discovered Enceladus (1789) and Mimas (1789). These were the only other moons discovered during the 18th century.

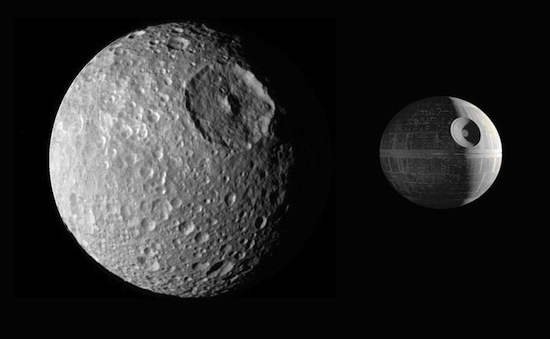

- Mimas is the "Death Star" moon, so named because its largest crater, appropriately named "Herschel" lends it an appearance resembling the famous planet destroying vessel that the empire has built and rebuilt and rebuilt throughout all 37 sequels and prequels.

.jpg%22&N=450px-Triton_moon_mosaic_Voyager_2_(large).jpg)

- Triton spews methane crystals out of geysers that erupt out of its methane ice surface. Voyager 2 captured the photograph above when it traveled through the Neptune system in 1989.

In 1848 Lasell and the two "Bonds," the father son astronomers named William Cranch and George Phillips, discovered Hyperion, another Saturnian moon. During the remainder of the 19th century, two more moons were discovered around Uranus, one more around Jupiter and another around Saturn. In 1877, Asaph Hall (1829-1907) found Phobos and Deimos, the only two moons known to be in orbit around Mars.

- Phobos (the inner moon) and Deimos(the outer moon) are both presumed to have been captured asteroids. Phobos completes one orbit around Mars every 7.5 hours. Deimos requires 30.3 hours to complete one orbit. Tidal forces will eventually demolish Phobos and its particles will form a ring around Mars. Phobos will eventually leave the Martian orbit.

It is highly likely that we humans will evolve into a star-faring race in the foreseeable, though not necessarily near, future. However, astronauts will have plenty of real estate to explore before we even set a toe around Alpha Centauri.

To subscribe or unsubscribe from the Daily Astronomer: