THE SOUTHWORTH PLANETARIUM

207-780-4249 www.usm.maine.edu/planet

70 Falmouth Street Portland, Maine 04103

43.6667° N 70.2667° W

Altitude: 10 feet below sea level

Founded January 1970

Julian Date: 2458849.16

Julian Date: 2458849.16

2019-2020: LXXVII

"We think we have a perfect vision of the new year."

THE DAILY ASTRONOMER

Wednesday, January 1, 2020

January 2020 Night Sky Calendar

Part I

2020!

MMXX!

A new decade begins and we can't wait to experience every second: while we don't know what will transpire in the roaring 20's as the war weary doughboys foxtrot with their sweethearts, we can predict most of the decade's upcoming celestial events, apart from solar flares, aurora exhibits, new comet apparitions, and other tricky cosmic matters that show us that nature remains annoyingly dominant. (We are almost four years away from the mega event: the 8 April 2024 total solar eclipse that will darken New England's skies, or, at least, darken the pervasive cloud cover we generally experience that time of year.)

However, the night sky never rests and the stars soaring above our heads know nothing of our calendar reckoning: what care those soarers for the New Year's ring? The Universe is merely and miraculously doing what the Universe does best: existing and working through its myriad motions while allowing all possibilities to slowly hatch out. We pick those events we smugly consider to be of the greatest interest and include them in our monthly calendar.

FRIDAY, JANUARY 3: FIRST QUARTER MOON

What? Does it seem a rather inauspicious way to usher in a new decade: something as quaint and quotidian as the quarter moon? It isn't We're beginning a new decade with the sight of a half moon: a lunar disc bisected by a razor sharp light-dark border that divides Earth's attendant world into a scorched land 200 degrees hot and a frigid one 200 degrees below zero. As the moon rotates only once every 27.4 days, the day-night line, called the terminator, creeps along at ten miles per hour at its equator (slightly less than five miles per hour at its equivalent of the Arctic Circle.) A biker could outpace the sunset at the equator as a jogger could close to its poles. Unlike Earth's sunrise, preceded by a gradual transition from subtle gray to vibrantly scarlet skies, the sun rise on the airless moon is immediate: a light switch quick jump from dark to light. Sunlight moving slowly but inexorably across an asteroid battered moonscape that bares its bruises for many millions of years. As you watch the first quarter moon, you'll see the deepest crater valleys awaken from a two week deep chilled night into a furnace hot morning. So, a first quarter moon isn't a boring way to start a decade. It is just a reminder that the only thing that doesn't exist is the cosmos is the ordinary.

SATURDAY, JANUARY 4: QUADRANTID METEOR SHOWER PEAKS

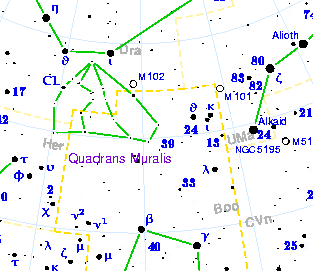

Meteor showers are generally named for the constellation from which the meteors appear to originate: for instance, the Perseids in August emanate out of Perseus the Geminids in December originate in Gemini. But the Quadrantids? That doesn't sound like any constellation in our sky. Well, it isn't. The Quadrantids appear to emerge from a region once known as Quadrans Muralis, a nifty little constellation crafted by uber-brilliant French astronomer Lalande in 1795. It depicted a wall mounted quadrant Lalande and his nephew used to chart the heavens. While Johann Bode included the constellation in his 1801 Uranographia star atlas, it was eliminated in the early 1930's when the International Astronomical Union conquered the heavens, formalized the list of 88 constellations and immediately punished dissent with oxygen deprivation.

An admittedly unimpressive image of Quadrans Muralis: an 18th century constellation depicting a wall mounted Quadrant. The now obsolete constellation resides in an area that the Big Dipper and Bootes now occupy.

The Quadrantids begin around December 28th and end around January 13th. They peak tonight. Look for the meteors to emerge from the area around northern Bootes. Unfortunately, the peak lasts only a few hours and the meteors tend to be fainter than most: dimmer than Polaris, the north star. Even though the peak should produce about 40 - 70 meteors an hour, this rich shower won't be as spectacular as it would if its meteors were brighter or if the peak lasted longer.

SUNDAY, JANUARY 5: EARTH AT PERIHELION

There is nothing to see here, unless you stare at the Sun (extremely bad idea) and measure its angular diameter. Were you able to do so, you would notice that the Sun is slightly larger in our sky now than at any other time of year simply because Earth is closer to it: about 91.5 million miles as opposed to the average distance of 93.5 million. Earth travels around an elliptical orbit, which, in our planet's case, is a slightly elongated circle. Consequently, Earth's distance from the Sun continuously changes from a minimum (perihelion) in early January to a maximum (aphelion) in early July. Today, we are as close to the Sun as possible in this orbit. As you might have noticed if you're standing outside listening to the blood in your ears congeal, this closer proximity to the Sun has little effect on our weather. However, our planet is revolving more quickly around the Sun now than it does in the summer due to this reduced distance. (The closer a planet is to the Sun, the faster it moves in accordance to the conservation of angular momentum.) For this reason, our winter isn't as long as our summer: something to buoy up our spirits as we warm our bodies over roasting mammoth carcasses.

FRIDAY, JANUARY 10: FULL MOON AND A PENUMBRAL LUNAR ECLIPSE (NOT VISIBLE IN EASTERN US)

The moon is full tonight! A bright, beautiful lunar disk looming majestically over the glistening snowsc....yeah. yeah, great...but, what about the eclipse we're not going to see? Tonight, the full moon will move through Earth's penumbra, the outer part of its shadow. Such an eclipse is noteworthy principally for not being noteworthy: a penumbral eclipse causes the moon's brightness to diminish slightly, or more correctly, imperceptibly. It won't be visible here, but, then again, even if it were visible, it would be largely invisible, so we're not seeing something we probably wouldn't have seen, anyway.

The moon is full tonight! A bright, beautiful lunar disk looming majestically over the glistening snowsc....yeah. yeah, great...but, what about the eclipse we're not going to see? Tonight, the full moon will move through Earth's penumbra, the outer part of its shadow. Such an eclipse is noteworthy principally for not being noteworthy: a penumbral eclipse causes the moon's brightness to diminish slightly, or more correctly, imperceptibly. It won't be visible here, but, then again, even if it were visible, it would be largely invisible, so we're not seeing something we probably wouldn't have seen, anyway.

January's full moon is curiously called the "Ice Moon," or "Snow Moon" or "Moon after Yule." We also know of it as the "Wolf Moon."

FRIDAY, JANUARY 10: MERCURY AT SUPERIOR CONJUNCTION

Let's play with our minds for a moment. Now, you are not sitting at your computer in rapt attention. Instead, you are poised "above" the solar system plane so you can see the Sun and its retinue of attendant worlds revolving around it. Since you're up here, I would recommend that you accelerate the planetary motions, make them appear brighter while at the same time dimming the Sun a bit so what you're observing doesn't actually blind you. Ok. What do you notice? The planets are all moving around the Sun at a steady clip. Granted, the closest planet, Mercury, is moving the fastest because it is closest to the Sun. Notice the third world: the bluish one? We're living there and as we move around, we notice that the planets occupy different positions relative to the Sun. These location changes are tricky because we're seeing moving objects from a moving platform. (It is for this reason that mathematical astronomy is not for the faint-hearted.) Now, in your mind, stop the motion when you see the clock read 10 January 2020. You will observe that Mercury is on the far side of the Sun relative to Earth. We refer to this configuration as "Superior Conjunction." Mercury is moving behind the Sun and won't be visible. Mercury will then move into the western evening sky.