THE SOUTHWORTH PLANETARIUM

207-780-4249 www.usm.maine.edu/planet

70 Falmouth Street Portland, Maine 04103

43.6667° N 70.2667° W

Altitude: 10 feet below sea level

Founded January 1970

Julian Date: 2458857.16

Julian Date: 2458857.16

2019-2020: LXXXII

"Meanwhile, back on Earth..."

THE DAILY ASTRONOMER

Wednesday, January 8, 2020

Wednesday, January 8, 2020

The Siberian Pole

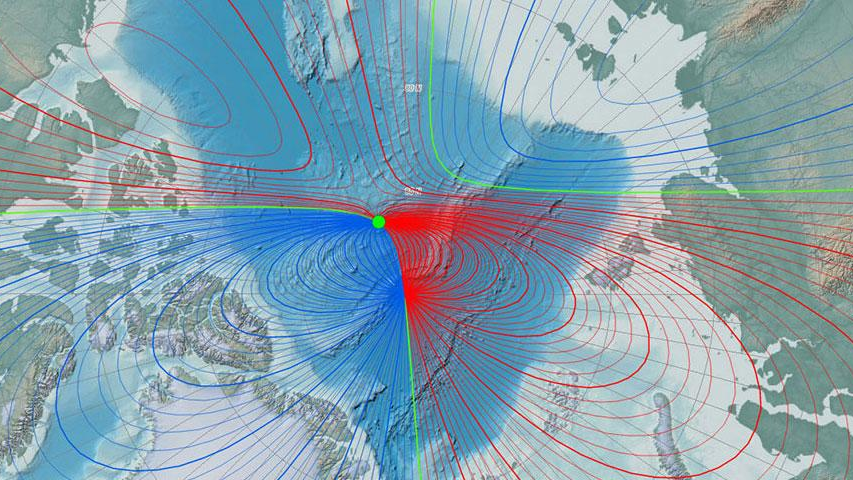

A September 2015 NOAA graphic pinpointing the magnetic pole almost at the true geographic north pole. This once lethargic pole shifted position by about 10 kilometers a year. Presently, its shift rate is about 40-50 kilometers an hour.

Yesterday we veered a bit far afield as we explored the most distant known exoplanets. Today, we remain Earthbound: specifically at Earth's apex, in the brutal north Polar region, where Earth's highly mobile and unseen magnetic pole is moving out of the high Canadian north where it has lingered for centuries and into northernmost Siberia. While the consequences of this shift from North America to Asia remains, the migration has captivated and even unsettled researchers who are confounded by the pole's directional change and rapid motion.

We know that on June 1, 1831, an expedition lead by James Clark Ross discovered the magnetic pole on the Boothia Peninsula around 72 degrees N latitude. In 1903, the famed explorer Roald Amundsen located it a different location, thereby demonstrating that the pole is mobile; it shifts position due to alterations in Earth's core. Within Earth's center one would find an ultra dense, incandescently hot iron-nickel core surrounded by a molten outer core about 100 times larger in volume than the Pacific Ocean. This core rotates at a slightly different rate than Earth,itself. This rotational motion combined with the vast electrons flows within the outer core behaves like a dynamo, generating the magnetic field enclosing our planet. (Electricity and magnetism are two aspects of a single fundamental force dubbed "electromagnetism.")

The magnetic pole was more lethargic in the past, traveling about 10 - 15 kilometers a year and following a generally northward trajectory. Within the last decade, this shifting has accelerated, reaching an estimated speed of slightly more than 50 kilometers a year. During the last ten years, the pole has maneuvered out of Canada and toward Siberia, moving from the western to eastern hemispheres. In September 2019, it was briefly aligned with the actual geographic north pole (a highly uncommon occurrence) before moving into Russia.

Earth's magnetic pole is a matter of grave importance to both humans and the society they've developed. First, a vast magnetic field enshrouds our planet, protecting us from the harsh radiation emitted by the Sun and more distant cosmic objects. Secondly, the navigation systems on which so much of our civilization depends is based on that field's strength and orientation. Consequently, the field is mapped and the pole location specified every five years with the World Magnetic Model produced by the British Geological Survey in collaboration with national environmental centers. The rapidity of the pole's motion induced them to deviate from their five year publication schedule to produce an early update in February 2019, representing only the second deviation in its history.

Scientists don't have a complete picture of Earth's magnetic pole and so are circumspect about offering any pronouncements about the magnetic field's future. (Although, they have noted a gradual magnetic field weakening, which could either be a precursor to a more dramatic event, such as a field "flip," or it could be a regular cyclical diminishment.) They know that the magnetic pole hasn't exhibited this much motion since records began, providing enough of an impetus to scrutinize it more closely.

While GPS systems should not be affected by this west to east migration, compasses could soon be directed east of north. Moreover, the farther away from us the pole drifts, the less frequent aurora displays will become. The closer one lives to the pole the more often one will tend to see the Aurora Borealis, as the charged solar particles that excite the atmospheric atoms to produce an aurora are drawn toward both the north magnetic pole. Of course, as the Sun has been more quiescent than expected lately, the aurora events might have been fewer and farther between, anyway.

Suffice it to say that we are not in any immediate danger; but in a world of constant change, it is wise to be wary of a pole moving so quickly on a planet that revolves through a neighborhood awash in harsh radiation.

To subscribe or unsubscribe from the "Daily Astronomer"